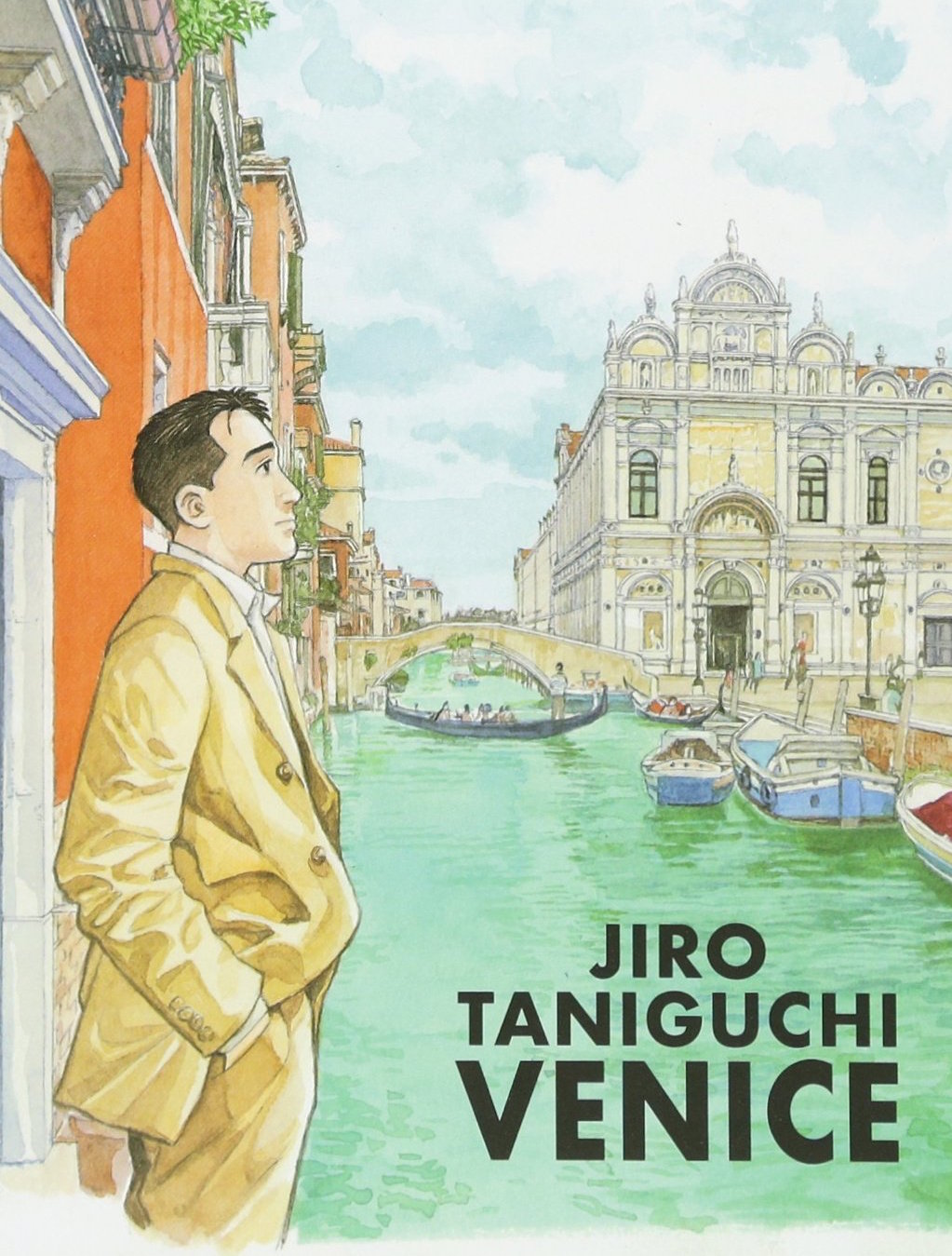

Venice — one of the last projects Jiro Taniguchi completed before his death in 2017 — is perhaps the most beautiful work he produced, a paean not only to the great Italian city, but to his own superb command of light, color, and line. Rendered in watercolor and ink, Venice‘s subtle palette and expansive treatment of the page are reminiscent of Taniguchi’s Guardians of the Louvre, while its premise recalls The Walking Man, Furari, and The Solitary Gourmet, three manga in which an unnamed male character strolls through the thoroughfares and byways of a major city, stopping to admire a blossoming tree or duck into an unassuming noodle shop.

Taniguchi makes an agreeable guide to Venice, frequently pausing to luxuriate in the very places that a visitor would find most charming: an outdoor marketplace filled with fruit and vegetable vendors, a moonlit promenade dotted with strolling couples, a faded but elegant hotel. Though Taniguchi renders these locations with the utmost precision, his most striking images are of canals and harbors. He captures the play of light on water with the same authority as a great maritime painter like Homer Winslow, using a watercolor palette of greens, blues, grays, blacks, and pinks to pinpoint the time of day and weather, as well as the tide — a small but potent reminder of Venice’s precarious relationship with the sea.

Though framed as a travelogue, Venice also explores similar thematic terrain as Taniguchi’s A Distant Neighborhood. Like the protagonist of Neighborhood, the Venetian wanderer is a middle-aged man making sense of his family’s past, a quest triggered by the discovery of a small lacquer box among his late mother’s possessions. A single image — a photo of a dapper Japanese couple feeding pigeons at the San Marco Piazza — leads him to Venice, where he retraces the couple’s steps. Taniguchi handles the mystery in an elegant fashion, eschewing pointed dialogue or voice-overs in favor of evocative imagery: a sepia-toned portrait of a family, a hand-drawn postcard of the Grand Canal. By focusing on these artifacts, Taniguchi provides just enough information for the reader to figure out who this young couple was without baldly explaining what drove them apart; only a brief inscription on the back of a postcard suggests the length and anguish of the couple’s separation.

These temporal shifts in the narrative are echoed in the way Taniguchi draws Venice itself. On several pages, for example, Taniguchi shows us familiar Venetian streetscapes as they looked in the 1930s, when the mystery couple lived there. On other pages, Taniguchi achieves a similar effect through the juxtaposition of the traditional with the modern: kayakers bob alongside gondoliers, floating past Renaissance merchants’ grand homes, while the mouth of the Canal de la Galeazze frames the arrival of a giant cruise ship. (In a nice touch, Taniguchi tracks the ocean liner’s stately progress over several panels, allowing us to appreciate its enormous size and sleek lines.) Even the most prosaic scenes emphasize the degree to which Venetians’ daily routines are shaped by its lengthy history; we see young children in baseball jackets sipping water from a fountain built in the 17th century and dog walkers chatting in the shadow of Venice’s great Campanille, unawed or unaware of these landmarks’ significance.

And while such sensuous images are fundamental to Venice‘s appeal, Taniguchi does more than recreate Venice’s great architecture; he conveys the rhythms and emotions of a journey, the experience of savoring new places while realizing in the moment that the place where you stand will be different the next time you visit. He evokes the curious sensation of déjà vu you experience in an unfamiliar city, as you see small elements of your own life reflected in the way that strangers live theirs. And he conveys the profound sense of discovery that comes from visiting a place that holds significance for a parent, lover, or friend, as you see the landscape through their eyes for the first time. That Taniguchi evokes these emotions primarily through the artful use of color and detail, rather than character development or dialogue, is testament to the depth of his artistry. Highly recommended.

For more insight into Venice, I encourage you to watch this brief video in which Taniguchi discusses the genesis of the story, and how he created some of the book’s most arresting images:

VENICE • BY JIRO TANIGUCHI • FANFARE/PONENT MON • NO RATING • 128 pp.