Short Cuts has the unique distinction of being one of the first manga I ever loathed. In fairness to Usamaru Furuya, I read it early in my relationship with manga, when the only titles I knew were Lone Wolf and Cub, Tokyo Babylon, InuYasha, Mermaid Saga, and X/1999. I found Short Cuts bewildering, frankly, as I knew very little about ko-gals — one of Furuya’s favorite subjects — and even less about the other cultural trends and manga tropes that Furuya gleefully mocked. Then, too, Furuya’s fascination with teenage girls, panties, casual prostitution, and incest grew tiresome: how many times can you play the am-I-shocking-you card before the shtick gets old? With the release of Genkaku Picasso, however, I thought it was a good time to revisit Short Cuts and see if I’d unfairly dismissed a great artist or correctly judged him as an unrepentant perv.

What I found was a decidedly mixed bag, a smorgasbord of jokes about girl cliques, lecherous salarymen, Valentine’s Day gift-giving, travel guides for foreigners, and, yes, sex. Some of the best strips tackle obvious targets in unexpected ways. Mr. Pick-on-Me, a recurring character, is one such example: he’s a robot whose sole job is to endure harassment from school kids, providing them a more attractive target for bullying than each other. He proves so effective, however, that the school administrators begin bullying him, too, necessitating the purchase of more robots. Another recurring character, Mitsu Cutie, is an assassin who assembles lethal weapons from bento boxes and Hello Kitty paraphernalia. Though Furuya is hardly the first person to wring laughs from a sweet-faced character’s degenerate behavior, the gag is surprisingly funny, not least for the way in which it carefully filters spy thriller conventions through the lens of shojo manga; it’s as if Takao Saito and Arina Tanemura teamed up to produce a story about a twelve-year-old hit girl.

Furuya is also a first-class mimic, capable of channeling just about any other artist’s style in service of a good joke. In one gag, for example, he twists a TV-addled teen’s face into a perfect imitation of Hitoshi Iwaaki’s parasite aliens, while in another, he shows a woman with ridiculously long eyelashes performing her daily grooming routine, revealing her true identity only in the final panel: she’s Maetel, the heroine of Leiji Matsumoto’s Galaxy Express 999. Even Tezuka take his lumps: in Furuya’s version of Astro Boy, the iconic robot looks like the rotund, bespectacled Dr. Ochanomizu, while his maker resembles Astro, though in Furuya’s telling, the mad scientist likes baggy knee socks, a hallmark of ko-gal fashion.

Furuya is also a first-class mimic, capable of channeling just about any other artist’s style in service of a good joke. In one gag, for example, he twists a TV-addled teen’s face into a perfect imitation of Hitoshi Iwaaki’s parasite aliens, while in another, he shows a woman with ridiculously long eyelashes performing her daily grooming routine, revealing her true identity only in the final panel: she’s Maetel, the heroine of Leiji Matsumoto’s Galaxy Express 999. Even Tezuka take his lumps: in Furuya’s version of Astro Boy, the iconic robot looks like the rotund, bespectacled Dr. Ochanomizu, while his maker resembles Astro, though in Furuya’s telling, the mad scientist likes baggy knee socks, a hallmark of ko-gal fashion.

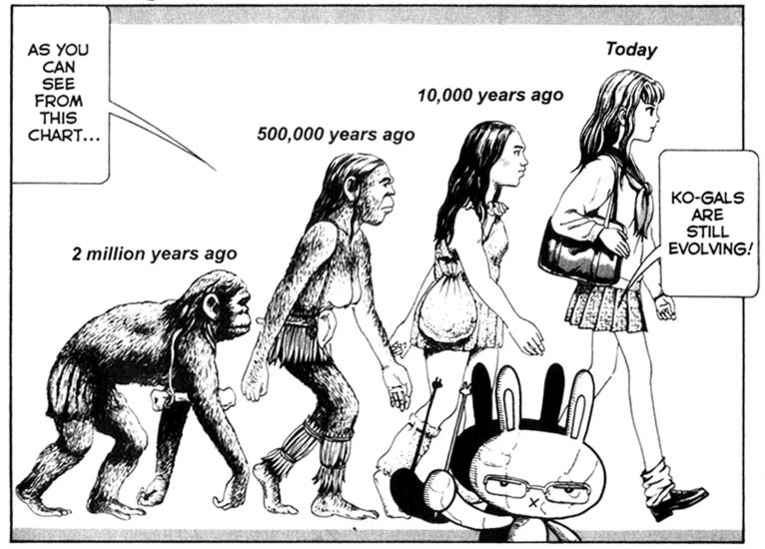

The Astro Boy strip is one of many poking fun at ko-gals, Japan’s own answer to the Valley Girl. Like their Orange County counterparts, kogals are an easy target: their speech and attire are distinctive and easily parodied, as are their devotion to shopping, brand names, and hanging out in the Shibuya district. That’s not to say that Furuya’s jokes are bad; to the contrary, there are some genuinely inspired panels. In one strip, for example, we see a shrine featuring monumental sculptures of ko-gals attended by elderly male priests in short skirts and baggy socks, while in another, a balding, middle-aged man apprentices himself to become a ko-gal, applying himself with the steely resolve of a samurai or geisha-in-training.

A lot of the ko-gal humor is rather mean-spirited, however, portraying girls as hopelessly dim, materialistic, and uninterested in sex unless it comes with a financial reward. Though the male characters are ridiculed for their willingness to pay teenage girls for sexual favors, Furuya allows the reader to have his cake and eat it, too, laughing with recognition at his weakness for panty flashes while being treated to… panty flashes. From very cute girls. Furuya even pokes fun at himself, punishing one of his female characters for her dawning awareness of his “Lolita complex.” (He first attempts to white her out, then resorts to drawing her as a monster.) In the final panel of the “cut,” he’s asserted control over the character again, blackmailing her into silence. The whole sequence is done with a nudge and a wink, as if to make us complicit in Furuya’s predilection for teenage girls; it’s a classic non-apology, the equivalent of saying, “No offense, but sixteen-year-olds are hawt, dude!”

In many ways, Genkaku Picasso seems like one of the two-page “cuts” dragged out to epic lengths. The story focuses on Hikari Hamura, a weird, asexual twit who becomes so involved with his sketch book that he finds a beautiful girl’s attention a nuisance. While sitting on the bank of a river with his classmate Chiaki, a bizarre disaster kills them both. She’s reincarnated as a pocket-sized angel; he’s reborn with a new supernatural gift, the ability to draw other people’s dreams. The central joke of the series is that Hikari is a terrible dream interpreter, reading even darker intent into other students’ nightmares than is implied by the imagery.

In many ways, Genkaku Picasso seems like one of the two-page “cuts” dragged out to epic lengths. The story focuses on Hikari Hamura, a weird, asexual twit who becomes so involved with his sketch book that he finds a beautiful girl’s attention a nuisance. While sitting on the bank of a river with his classmate Chiaki, a bizarre disaster kills them both. She’s reincarnated as a pocket-sized angel; he’s reborn with a new supernatural gift, the ability to draw other people’s dreams. The central joke of the series is that Hikari is a terrible dream interpreter, reading even darker intent into other students’ nightmares than is implied by the imagery.

The need to show where Hikari’s interpretations go astray proves Genkaku Picasso‘s biggest weakness. Consider “Manba and Kotone,” the third story of volume one, in which one of Hikari’s classmates is plagued by images of a teenage girl being tortured and tied up. As Ng Suat Tong points out in his review of Genkaku, the punchline is squicky: these images aren’t a dark fantasy, but pictures from a magazine shoot in which the girl volunteered to pose for her father, a professional photographer. Handled in two panels, the joke would hit like a nasty rim shot, but as the driving force behind the chapter’s storyline, it becomes… well, seriously creepy, pushing the material into the decidedly unfunny territory of incest and parent-child power dynamics.

I actually liked Genkaku Picasso more than Tong did, partly because I think Furuya is having a ball subverting shonen cliches; it’s the kind of series in which doing your best means staving off body rot, not winning a tournament, and a quiet, philosophical moment between two teens is interrupted by a fiery helicopter crash. I also liked some of the dream sequences, which showcase Furuya’s incredible versatility as an artist. However pedestrian the script may be in explaining the images’ meaning — and yes, there are some borderline Oprah moments in every story — the dreams are nonetheless arresting in their strange specificity.

After reading Short Cuts and Genkaku Picasso, I’m convinced of Usamaru Furuya’s ability draw just about anything, and to tell a truly dirty joke. I’m not yet persuaded that he can work in a longer form, but perhaps if he’s adapting someone else’s story — say, Osamu Daizi’s No Longer Human — he might find the right structure for containing and directing his furious artistic energy.

Review copy of Gengaku Picasso provided by VIZ Media, LLC.

SHORT CUTS, VOLS. 1-2 • BY USAMARU FURUYA • VIZ • NO RATING (MATERIAL BEST SUITED FOR MATURE READERS)

GENKAKU PICASSO, VOL. 1 • BY USAMARU FURUYA • VIZ • 192 pp. • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)

John Jakala says:

Hmm, I remember loving Short Cuts but it’s been a long time since I looked at it. Maybe I should dig it out and give it a second look too.

I’ve been looking forward to Genkaku Picasso but the excerpts from Tong have me worried that it’s going to be unnecessarily creepy.

Katherine Dacey says:

Hi, John! Your manga-blogging presence is sorely missed!

I didn’t hate Short Cuts; as I hope I made clear, I enjoyed a lot of the strips. But I have to admit, I was bothered by Furuya’s obsessive interest with teenage girls. There was something pretty unsavory about it, both for the fact that teen girls are an easy target, and for the author’s prurient interest in them.

Jade says:

I really liked Genkaku Picasso, but even by the end of the volume I could see that Hikari might never really develop. I thought his misinterpretations were hilarious, but I don’t know how many volumes I could put up with him being completely self-centered and wrong. Like you said, this is a send-up of that sort of boy though, so I’ll have to see if the laughs can hold up.

I’m actually more interested in Chiaki. She has a surprisingly sophisticated personality for a role that would otherwise be stock manic pixie dream girl. I’m almost rooting for her to just leave Hikari to rot. :3

Katherine Dacey says:

I agree that there’s more going on here than Tong allowed in his review; some of Hikari’s dream misreadings were pretty funny (if kind of tasteless). This seems like a 3-volume title at best; much longer than that, and it risks alienating the reader or repeating itself too much.

Ahavah says:

I’ve never heard of Short Cuts before. Is it still in print? I’m looking forward to Genkaku Picasso, and all I can say after reading your review is that “I hope Shonen Jump’s standards kept the manga-ka from writing way too creepy or mysogynistic stories.” But I’ve read Shonen Jump manga before, and if a manga-ka wants to be creepy and mysogynistic, he’s got every right to be. Makes me wonder why so many young girls in Japan love Jump, and if Jump has ever had a female author serialize a major title for them, come to think of it. That’s how I feel Shonen Sunday keeps a co-ed audience, anyway. (if you put InuYasha in a magazine for girls and renamed it “Kagome,” would anyone notice?)

Katherine Dacey says:

@Ahavah: Short Cuts is out of print, though the second volume is pretty easy to obtain through Amazon’s network of sellers. I bought both volumes on eBay for about $10.

Good question about Shonen Jump: offhand, I don’t know of any female creators who’ve written for that magazine, but I’m sure someone in the mangasphere can correct me if I’m wrong. I’m more partial to Shonen Sunday titles for pacing reasons: I find a lot of SJ titles too “caffeinated” for my taste, if that makes sense.

Ahavah says:

Come to think of it, I’ve heard that D. Grey Man is written by a woman, although I can’t comment on that title specifically as I’ve never read it. I enjoy many Jump titles, but I find them lacking when it comes to strong female characters, an archetype I appreciate in any type of manga. Unfortuantely, they tend to be few and far between.