Do you remember those first, glorious seasons of Heroes and Lost? Both shows promised to reinvigorate the sci-fi thriller with complex, flawed characters and plots that moved freely between past, present, and future. By the middle of their second seasons, however, it was clear that neither shows’ writers knew how to successfully resolve the conflicts and mysteries introduced in the first, as the writers resorted to cheap tricks — the out-of-left-field personality reversal, the all-too-convenient coincidence, and the arbitrary let’s-kill-off-a-character plot twist — to keep the myriad plot lines afloat, alienating thousands of viewers in the process. Heroes and Lost seemed proof that even the scariest doomsday scenario would fall flat if saddled with too many subplots and secondary characters.

Reading Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys, however, convinced me that it is possible to tell a twisty, layered story about ordinary people saving the world from annihilation without succumbing to cliche or unduly testing the audience’s patience. The key to Urasawa’s success? A strong script with vivid characters and a clear sense of purpose, reassuring the reader that all the plot strands are just that: strands, not loose threads.

In 20th Century Boys, humanity’s future rests in the hands of an unpromising lot. There’s Kenji, a college dropout who runs a convenience store; Maruo, a cheerful, plump soul who owns a shop down the street from Kenji; Yoshitune, a shy, bespectacled office man; Otcho, a scruffy renegade who’s been living off the grid in Thailand; and Yukiji, a K-9 officer who can’t control her drug-sniffing dog. All five were childhood friends, members of a secret club that wrote The Book of Prophecy, an elaborate doomsday scenario involving superheroes and giant robots. Now in their thirties, the gang has disbanded — that is, until their pal Donkey, a high-school science teacher, leaps to his death off a building.

Or did he? As Kenji begins pushing for answers, he discovers that Donkey was investigating a mysterious cult, known only as The Friends, that had appropriated the club’s “official” symbol. The more Kenji probes, the more parallels he discovers between The Friends’ clandestine activities and the Book of Prophecy, parallels that suggest the cult is headed by one of Kenji’s old schoolmates. Terrified that The Friends will attempt to recreate the story’s climatic battle, Kenji tracks down his clubmates one by one, assembling a small army to oppose the cult.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

From the very first pages of volume one, Urasawa demonstrates an uncommon ability to move back and forth in time, juxtaposing scenes from Kenji’s past with brief glimpses of the future. The success of these scenes is attributable, in part, to Urasawa’s superb draftsmanship, as he does a fine job of aging his characters from their long-limbed, baby-faced, ten-year-old selves into thirty-somethings weighed down by adult responsibilities.

The integrity of Urasawa’s characterizations also contribute to the success of these temporal leaps; his characters’ adult behavior jives with what we know about them from childhood flashbacks. Otcho, for example, was the club’s most worldly member, the kid who introduced his pals to rock-n-roll and gave them the lowdown on Woodstock; it’s not surprising to see him reincarnated as a long-haired thug-for-hire who despises authority. Ditto for Yanbo and Mabo, twins who terrorized Kenji and friends back in the day. When Yanbo and Mabo resurface in volume five, Urasawa gives them a more pleasing appearance and demeanor than we might have expected, luring us into a false sense that they’ve outgrown their bullying ways. Urasawa then slaps us on the wrist for not trusting our original assessment of the twins, uncorking a fiendish plot twist that’s in keeping with what we already knew about them.

Urasawa uses these flashbacks and flash-forwards to build a dense network of connections among his characters, gradually revealing how and why Kenji’s childhood fantasies are providing the blueprint for a real-life apocalyptic scenario. Heroes and Lost attempted to do the same thing, but neither show succeeded in convincing us that those connections were lying just below the surface waiting for us to discover them; those connections had an arbitrary, bolt-from-the-blue quality. With 20th Century Boys, however, Urasawa makes us feel that we might have unearthed these links without any editorial guidance, as even the most surprising developments still make sense within the story’s elaborate framework.

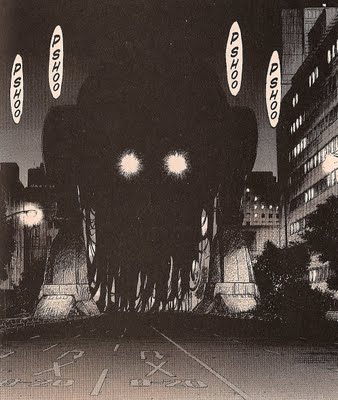

What gives the story its sense of urgency is Urasawa’s ability to create and sustain a strong sense of fear and anticipation. Six volumes into 20th Century Boys, we’ve had a few tantalizing glimpses of the robot that menaces Tokyo on the eve of the millennium, but we still don’t know what it looks like or what it can do. Urasawa has only shown us the enemy in silhouette:

It’s a point I’ve raised in other reviews: an unseen menace is much scarier than one that’s routinely trotted out of the shadows to spook us. Consider the difference between Jaws and its sequels. In the original, Steven Spielberg hinted at the shark’s presence, showing us a dorsal fin or a dark outline moving rapidly beneath the water’s surface, but withholding the “money” shot (“tooth” shot, perhaps?) until the third reel. The few times that we see Jaws attack are genuinely scary because they finally put us face-to-face with those terrible teeth and dead eyes, confirming just how deadly the shark really is. In the sequels, however, the shark is featured prominently; we see it dine on boaters and swimmers in lurid detail. We may marvel at the stupidity of the shark’s victims, or feel disgusted by the gallons of fake blood, but we never feel scared, as we know what we’re up against from the very first scenes.

Urasawa takes a page from Spielberg’s book, showing us just enough of the robot’s form to engage our imagination. The robot’s silhouette hints at its size and strength; if anything, it looks like an enormous man-o-war lumbering through Tokyo. But what stays with us are those fierce, penetrating headlights, so evocative of a prison searchlight or a pair of eyes. As David Ford observes at Are You a Serious Comic Book Reader?, we feel a palpable sense of despair when we see the robot: how can Kenji hope to escape its all-seeing gaze? (By the way, I highly encourage you to read Ford’s essay, though spoiler-phobes should stay away until they’ve finished volume five.)

With more than ten volumes left in 20th Century Boys, I have no idea how Urasawa plans to tie all of the stories’ threads together. I’m confident, however, that he’ll do so with the skill of a master weaver, seamlessly incorporating all of the relationships, plot twists, and motives into an intricate, beautiful tapestry.

Review copies provided by VIZ Media, LLC. Volume seven will be released on February 10, 2010.

20TH CENTURY BOYS, VOLS. 1-6 • BY NAOKI URASAWA • VIZ • RATING: OLDER TEEN (16+)

Sorry to be a pain, but it appears that 20th Century boys is 22 volumes long (with and additional 2 volumes for 21st Century boys, its epilogue/wrap-up). Still, more space for the plot to breathe.

While I agree whole-heartedly about the sheer terror the that the robot evokes, but I have a slight issue with it. I reached a point in Volume 5 where my tension was at its maximum, I was as scared of it as I could be, and no matter what it was revealed to be I would have been completely and utterly satisfied. Then, the monster was *not* revealed. Instead, the series does a rather large scene shift and I am left with my sense of anticipation and dread deflating. Now the storyline is set after the robot’s actions and I find my interest in the robots reveal sadly gone.

I have read as much as you have (read the 6th volume in the week) and still look forward to seeing the other plot threads develop but after this non-reveal of the robot I feel rather jaded about the series – how long am I going to have to wait for answers of any kind?

Guess I’ll have to keep reading to find out.

I’ve already fixed the reference to the series’ length — I’d confused it with Pluto. (You may have clicked on the review before I caught the error.)

As for volume five… well, I guess we all have different expectations for how and when the robot/monster should be revealed. I was satisfied with the way Urasawa handled it, but I can also completely understand why other readers might not be. I think it helped that I sat down and read all six volumes in an afternoon; I might have been more frustrated if I had waited several months between reading volumes five and six.

I clicked on the article link as soon as it was posted to twitter. 🙂

It’s not just the delay between volumes – I read vols. 3 to 5 in one afternoon after a manga purchasing binge. The thing that irks me the most is the amount of build-up, and from now on the “Robot reveal” will not have the same effect (at least for me) as it would have had if it had been revealed in Volume 5 just before the time skip.

If the robot is shown in an upcoming volume, what relevance will it have?

Unless a similar situation arises, the big event of which it was the star has been and gone now (at least in the flow of the story) and the world we are shown has firmly moved on to a time set after it has played its role and left. (I am being vauge on purpose here and not mentioning exact events to prevent spoilers)

Hell, we even saw a tantalising board meeting (The only time those three words will go together as such) about the design of the robot! That was a masterstroke of tension building, but now looking back feels like a massive tease.

As an aside, how do you expect to the robot to be revealed? You mentioned differing expectations and I’d like to hear what you think as honestly I feel like some raging nutcase about now.

The other repercussion of this reveal, I feel, is you have to wonder how other mysteries in the manga will be handled? While I dearly love Urasawa’s other works and have great faith in his storytelling abilities I have a nagging worry that a lot of answers are going to be withheld until the reader is sick of waiting for them.

I don’t think you’re a raging nutcase! I’ve felt the same way about other series — just get to the point, already! — but not 20th Century Boys. So far, at least, I feel like the story is headed someplace, and I have some idea of what The Friends ultimately plan to do with the big robot (at least on the eve of the millennium). I don’t have a clear expectation for how the robot should be revealed, but when: I want a better sense of what the 21st century looks like before I finally learn what went down on 12/31/00. I could hold out for at least four or four more volumes without seeing it, I think.

Your comments point to one of the trickiest aspects of this kind of genre: with a Baroquely complicated plot, the author needs to reward his reader from time to time with concrete information. I bailed out on Lost because I got the distinct feeling that the writers had absolutely no idea what to do after the hatch was opened, and just started winging it. I have much greater confidence in Urasawa’s storytelling abilities, though I agree that by the midway point in the series, we should feel like he’s beginning to answer more questions that he’s posing.

Having read 20th Century Boys, I can safely say Urasawa will not leave his unreveals unanswered for too long. Knowing the length of the series, and only having a limited scope of the major elements and mysteries involved makes it look like he’s going to have to spread it thin to make it the rest of the stretch.

But we’ve hardly scratched the surface. Urasawa will leave you hanging just long enough to weave his newly introduced threads back into the thread he left you with. In this way it’s similar to Monster, though Monster did it primarily with characters.

To be fair, it’s easier to twist up the plot by yourself than it is with a team of writers.

I love this series, but the setting shift is really jarring and leaves no clue as to whether or not the story didn’t just fly off the rails. With that in mind, it’s almost unfair to lump that part of the story in with the first portion. Five and six seem more like a long drawn out red herring so far.

Wah, I want to read the rest of it. I’m pretty sure I know who Friend really is now, but who knows how long it’ll be until I can confirm it.

VERY MINOR SPOILER ALERT BELOW… WARNING TO OTHER READERS WHO AREN’T UP TO DATE ON 20TH CENTURY BOYS!!!

@Jade: Collaborating with the same editor for years helps keep the whole enterprise on track, I’m sure. I also think it helps that Urasawa didn’t face the same pressures as a team of network television writers, who have no way of knowing whether or not their story will be picked up for future seasons.

I agree that the time shift in volumes five and six was bracing, but I have to admit, I kind of liked it. Seeing Kanna as an adult was fun, and a nice payoff for the prelude in volume one. As long as Urasawa isn’t using this detour to delay a super-obvious conclusion, I’m OK with it.

WARNING! RESPONDING TO MINOR SPOILER ALERT!

@Katherine: Don’t get me wrong, I do enjoy what’s going on after the shift. The future characters are also some of my favourites. You really feel more sympathy with them since their ideals are fresh and untainted, where the original cast hit the stage at the low point of sacrificing their ideals to conform to the system. It’s definitely interesting to see heroes climb up from the bottom of the barrel, but what’s really clever with the future cast is they can still play off that journey from the depths while hitting the stage as innocents and injecting new blood.

I’m just not sure there was enough internal assurance from Urasawa that he didn’t just get sick of the last story and completely switch gears. As a fan of Urasawa, I can assume otherwise, but considering how often older manga series can completely fly off the rails, as a manga fan, I need a little something to tell me a story isn’t doing the same thing manga tends to do. It’s not you, Urasawa, it’s me, heehee.

Having already read the entire series, all I can say is good on yo ufor making your call 6 volumes in. Please revisit this post once you’ve finished 20th Century Boys and let us know if your opinion has changed.

I don’t know if that’s a criticism or a suggestion, adante, but I certainly plan to revisit 20th Century Boys to see if I think the ending matches the beginning in terms of quality and logic.

Yeah – I don’t want to spoil it by allowing you to infer something from what I _want_ to say, so I deliberatelly made it cryptic 🙂

Thank you for your restraint, adante! I am *dying* to know how it all turns out, and can’t believe there are another sixteen or so volumes to go in the series. VIZ can’t release ’em fast enough, IMO. (If I could read Japanese, I’d have probably read the whole thing twice by now.) I thought he did a good job of sustaining Monster over eighteen volumes, so I’m cautiously optimistic that I’ll be happy with the ending of 20th Century Boys.