Last weekend, I had an opportunity to visit the San Francisco Public Library, which is mounting a small but meticulously curated exhibit exploring the relationship between politics, censorship, and manhwa in post-war Korea. Called “Korean Comics: A Society Through Small Frames,” the exhibit features twenty-one of Korea’s best-known cartoonists, from Kim Won Bin, creator of Fist Boss, to Hwang Mina, a sunjong (girls’) pioneer. For a Western reader whose primary knowledge of manhwa comes from titles such as Goong: The Royal Palace, the exhibit will be revelatory, as almost none of the series on display look like the Korean comics that have been licensed for the US market; if anything, the curators have gone out of their way to choose titles that challenge the commonly-held Western notion that manhwa is simply the “Korean form” of manga.[1] Styles range from the cartoonish (Baby Dinosaur Tuli, Madame Vicious) to the naturalistic (The Picture Diary of Puja), while the story lines explore topics as varied as ancient Korean history (Kojudo: Three Kingdoms), homelessness in Seoul (We Saw a Pity Bird Who Lost Its Way), Korean involvement in the Vietnam War (Yellow Bullets), and sumo champion Rikidozan, who is credited with introducing Japanese and Korean audiences to modern professional wrestling.[2]

Throughout the exhibit, curators have gone to great pains to illustrate the complex relationship between cartoonists and the Korean government, noting when a particular title elicited criticism from officials or earned praise for its depiction of Korean life. Visitors unfamiliar with recent Korean history may be surprised to discover the degree to which propaganda and censorship shaped the development of manhwa in South Korea. Hwang Mina’s We Saw a Pity Bird, for example, caused a stir when Seoul was preparing to host the 1986 Pan-Asian Games; the government attempted to ban the work for depicting poverty and homelessness in urban settings, fearing that Pity Bird would make South Korea look economically backwards. Other works, such as Kim Seong Hwan’s Koban, a long-running newspaper strip, ran afoul of Park Chung Hee’s censors for depicting student unrest and changing social mores in the 1960s.[3]

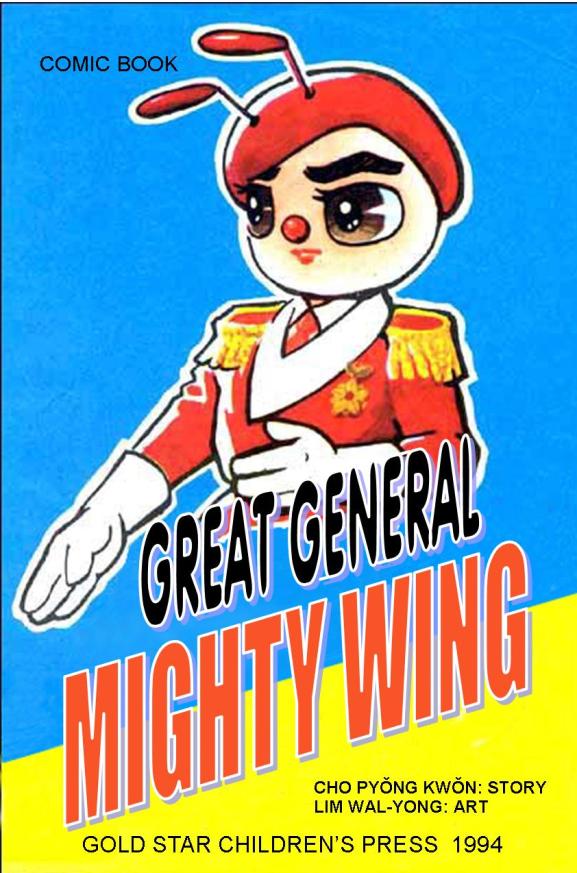

Not surprisingly, the exhibit’s most dramatic illustration of the relationship between comics and politics comes from North Korea. The Great General Mighty Wing debuted in 1994, shortly after Kim Jong Il succeeded his father. Like Soviet novels of the 1920s and 1930s, and Chinese model operas of the 1960s, The Great General Mighty Wing is intended both as entertainment and education, employing a popular medium to teach Communist values, assert the importance of the collective, and reassure readers of their leader’s benign, parental authority. Using the metaphors of the garden and the hive (both Communist staples), the story depicts a conflict between honeybees and wasps for control of two vital resources: water and flowers. The full-color artwork is a synthesis of mid-1950s Korean and Japanese styles (Fist Boss is cited as one important influence), while the script is pure agit-prop, with characters speaking in Communist slogans and heroic, selfless pronouncements.

One of the subtler affects of censorship — artistic isolation and stagnation — is addressed briefly but effectively in the few examples of sunjong manhwa on display. Korea experienced a brief shojo manga boom in the 1970s, when pirates flooded the Korean market with unauthorized versions of popular Japanese titles. The Magnificent 49ers’s style, in particular, had a profound influence on artists writing for the girls’ market. After the government cracked down on Japanese imports, however, Korean artists who had drawn inspiration from the 49ers no longer had access to current shojo manga; as a result, variations on the starry-eyed heroines and long-haired princes of The Rose of Versailles flourished in Korean manhwa long after they’d fallen out of fashion in Japan.[4]

If I had one complaint about the exhibit, it’s that visitors whose entire knowledge of Korea is rooted in the present may not appreciate the degree to which the displayed comics reflect the social and political upheaval of the past eighty years. A small timeline of major events, or even a pamphlet providing a brief overview of Korean history from 1939 to the present, would have been a valuable asset to the exhibit. (A quick glance at the Wikipedia articles on Korea, North Korea, and South Korea are strongly suggested if you don’t know much about the region.) That said, “Korean Comics” is a thoughtful and thought-provoking show that will challenge readers’ notions of what manhwa is, offer them a window into Korean society during some of its most turbulent periods, and introduce them to twenty-one brilliant artists, all of whom deserve greater recognition outside their home country.

“Korean Comics: A Society Through Small Frames” runs now through June 13, 2010 at the Main Branch of the San Francisco Public Library. Admission is free. For hours and directions to the library, click here. The exhibit is a joint effort by the San Francisco Public Library and the Korea Society.

Suggested Reading

“100 Years of Korean Manhwa,” Park In-Ha. List: Books from Korea (Vol. 4, Summer 2009). (Accessed April 9, 2010.)

“Great General Mighty Wing,” Cho Pyong Kwan; translated by Heinz Insu Fenkl. Words Without Borders: The Online Magazine for International Literature (February 2, 2008). (Accessed April 8, 2010.)

Manhwa 100: The New Era for Korean Comics. NETCOMICS (2008). Available through Amazon and other retailers.

A Study of the Development of Sunjong Manhwa by Hwang Mina, Kim Hyerin, and Choi In-sun, Yeewon Yoon. Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia (2002). Available through the UBC Retrospective Theses Digitization Project [http://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/retro_theses/]. (Accessed April 9, 2010.)

Notes

1.This disparity is reflected in the library’s suggested reading list, which features a number of contemporary works such as The Antique Gift Shop, Honey Mustard, Moon Boy, and Priest but none of the works feature in the show. The SFPL’s collection does include a few Korean-language titles, which are listed in the bibliography.

2. Rikidozan is mentioned in Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s A Drifting Life (2009; Drawn & Quarterly), in which Rikidozan is presented as a Japanese hero for defeating American wrestlers in the ring. See pages 261-63.

3. Kim Seong Hwan produced 14,319 Koban strips over its 50+ year run in Korean newspapers.

4. NETCOMICS, a Korean publisher which has been translating manhwa for the American market, has released a number of sunjong titles from the 1980s and early 1990s that suggest the continued influence of 1970s shojo styles on Korean artists. The early work of Kyungok Kang provides an instructive example. See In the Starlight and Narration of Love at 17 for two such examples; her later work, such as Two Will Come, has a distinctly different look.

Sara K. says:

Hey,

I also visited the exhibit this week. I also attended the lecture they had a few weeks ago, which included a brief introduction to 20th Century South Korean political history, so I was probably more clued into the social-political references than most non-Korean visitors.

Andrew Farago did the descriptions? I didn’t know that. I assumed, since this is a traveling exhibit of the Korea Society that the Korea Society did all the descriptions, but I suppose they might have asked him to do it for them, or they might have been made just for the San Francisco stop.

I also missed the suggested readings … I’m surprised that “Buja’s Diary” didn’t make the list, considering that it is featured in the exhibit as “The Picture Diary of Puja” *and* it’s available at the SFPL in English.

Also, the single most impressive page in the entire exhibit, to me, was

“I Am a Flower”. That is a powerful visual metaphor.

Katherine Dacey says:

I was surprised to see that Buja’s Diary wasn’t on the list, either, but since I don’t live in SF, I didn’t spend any time exploring the online catalog to see what was in the collection. The list was pretty eclectic — a lot of the suggested readings on comics don’t address manhwa at all, while lion’s share of manhwa titles are squarely aimed at the teen girl market. Maybe it was designed to be a complement to the talk given on April 8th?

As for the show, Andrew Farago is identified on the SFPL website as the curator. I don’t know what, exactly, his role was in selecting and presenting the comics on display, so I’ve clarified the language in the article a little bit. (Well, “vague-ified,” to be more precise!)

Sara K. says:

I didn’t see Andrew Farago credited as the curator on the SFPL website. Could you link? I know that when he was in the panel they said he was a curator, but I thought that referred to his work at the Cartoon Art Museum, not this exhibit.

Anyway, the sunjeong section was one of my favorites. I think Four Daughters of Armian had the prettiest artwork in the whole exhibit. It actually reminded me more of Colleen Doran rather than the 49ers themselves, which makes sense as both Doran and Shin Il-Suk were 80s non-Japanese female artists heavily influenced by the 49ers. Also, they seem similar in that they focused a little less on romance than a lot of 70s shojo manga. However, Rose of Versailles does have a revolution, and in the lecture I attended the speaker described the image as ‘a strong woman protecting her (male) lover’ so Four Daughters of Armian is not romance-free. The image shown is the lecture is the same one at this website: http://www.hani.co.kr/section-014009000/2000/014009000200006281157001.html

Katherine Dacey says:

That information appeared on the SFPL’s website announcing the talk that he, Mike Madrid, and Trina Robbins gave on April 8th. Here’s the link: http://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=1000502401. Since his role at the Cartoon Art Museum was not specifically mentioned, I assumed — perhaps wrongly — that the term “curator” indicated his involvement with the show. Unfortunately, I live in Boston, so I can’t go back to the show for another look around. If I get definitive confirmation of who wrote the exhibit text, or who is credited with curating the show, I will post that information here.

Sara K. says:

At the exhibit, they gave clear credit to the Korea Society, but not to Farago, and since it is a traveling exhibit and clearly prepared by people who know Korea well, I suspect Farago contributed little.

Anyway, I just went to a library branch to return some books, and seeing that Buja’s Diary was on the shelves, I finally got around to checking it out. I was actually struck by how much manhwa there was on the shelves – Antique Gift Shop, Chocolat, etc … I also know that the SFPL also has a bunch of manhwa in Chinese as well.

Aside from the sunjeong, my favorites were the political stuff (possibly because it was short enough to be complete – I might love Fist Boss if I could ever read enough to get a sense of the story). Unfortunately, I think it is unlikely to ever become available in English due to the cultural barrier. So I’ll keep rooting for 80s sunjeong. One of the artists mentioned in the exhibit, Kyungok Kang, is actually well represented in English thanks to Netcomics. I should try some of her stuff.